By: Cynthia Sommer

The 100th Anniversary of the City of Milwaukee Forestry Section is a reason to celebrate and recognize its contributions to our quality of life. In Murray Hill, we are enriched with many city street trees (> 1,750), numerous private properties trees, and Newberry Boulevard tree-shaded open space. We have the bonus of our surrounding green spaces and trees in Lake and Reservoir Parks, Oak Leaf Trail, Rotary Centennial Arboretum, Downer Woods and UW-Milwaukee green spaces. How easy is it, in our busy world, to take for granted the beauty and the many benefits of our trees! We may not even be cognizant of how our green world was developed.

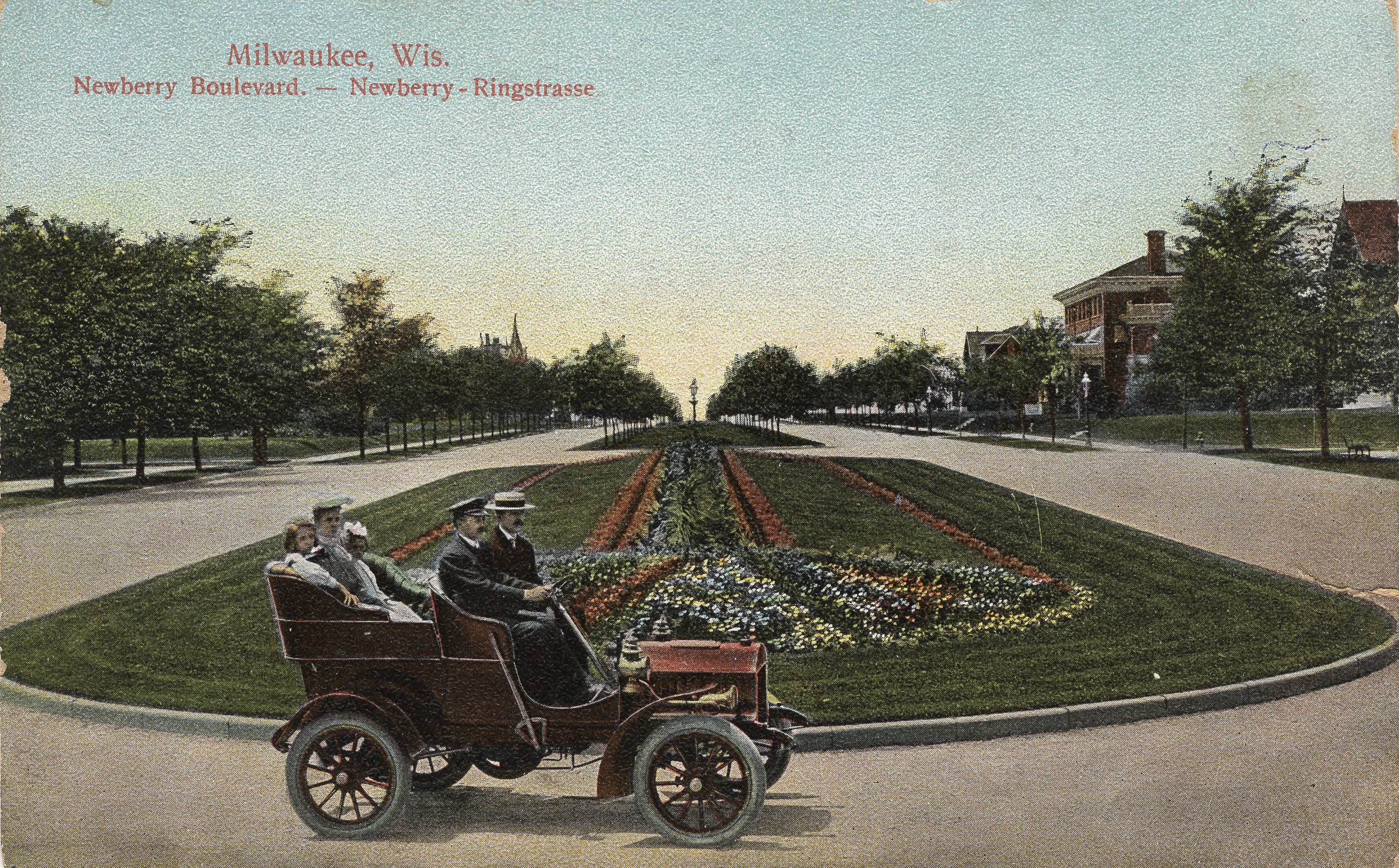

Newberry Boulevard Then (Lake Park Entrance to Newberry Boulevard from a 1905 postcard of a young, prosperous, chauffer driven family. Photo courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library Digital Collection)

David Sivyer, City of Milwaukee Forestry Manager, shared with me in an informative interview that the City Forestry Section alone maintains over 195,000 trees on 1,400 miles of streets and 120 miles of landscaped boulevards. The City nursery in Franklin maintains 160 acres with 20,000 growing trees and over 30,000 sq. ft. of greenhouses that produces 200,000 annuals and perennials yearly. The staff strives to prune the City street trees on a 6-year cycle.

Newberry Boulvard Now (Lake Park Entrance to Newberry Boulevard in 2018 with many mature trees. Photo by Cynthia Sommer)

Our City Forestry has a unique accomplishment and a serious commitment to trees—98% of planting spaces that can support a street tree, have a tree. Most cities have a 60-70% stocking rate. Our City has been identified by the Arbor Day Foundation as a Tree City USA for 39 consecutive years and the American Forest Association (AFS) recognized Milwaukee in 2013, as one of the 10 “Best Cities for Urban Forests.” The Association recognized that the City of Milwaukee Forestry “cares for and maintains the health of its trees, has a comprehensive inventory of trees, a tree diversification plan, civic engagement, citizen accessibility and strategies to help address city infrastructural challenges.” These accomplishments by many dedicated staff are the story of the Forestry Program

in Milwaukee.

At the end of the 19th century and before the establishment of the City Forestry Section in 1918, the City Parks Commission directed the development of green spaces in the City. When Newberry Boulevard was being developed, the residents were asked to purchase trees for their street spaces. The first City Forestry census in 1921 counted 82,392 street trees—most planted by property owners. The spacing, care and types of trees, however, were not always appropriate and

validated the need for City arborists. During the Depression in the 1930s, the federally funded Works Progress Administration helped to build many of the greenhouses in Franklin.

The serious challenge to the City Forestry Section came in the 1950s with the arrival of Dutch elm disease (DED). According to Greening Milwaukee, the first case of DED was detected on the East Side of Milwaukee in 1955 and quickly

The serious challenge to the City Forestry Section came in the 1950s with the arrival of Dutch elm disease (DED). According to Greening Milwaukee, the first case of DED was detected on the East Side of Milwaukee in 1955 and quickly

spread throughout the City. Vigorous efforts of cutting dead trees, spraying for the beetle and tree treatment were launched to save the many beautiful American elm trees in the City. Even the police and fire budgets were cut to pay for the fight to save the trees. David Sivyer estimates that of the 106,000 elm street trees in the City in the 1950s, less than 400 trees remain today. Neighbors are fortunate to be able to still see on their walks in the neighborhood some large surviving American elm trees with their beautiful arching canopies, for example, at 2550 N. Prospect and 2833 N. Frederick Avenues.

Much of the work of the City Forestry Section in the 1960s, 70s and 80s was diverted to handling the demanding Dutch elm disease problem. Yet, forestry staff were still able to expand the landscaped boulevard system, develop a computerized street tree inventory, start the continuing tradition of the Tree City USA award and initiate the resident donated City Christmas tree program.

The knowledge gained from Dutch elm disease and the arrival of the first US documented case of the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) infestation in Detroit in 2002 led to early proactive measures by the City Forestry staff. In 2009, the Milwaukee Forestry team used emergent remote sensed hyperspectral imaging along with US Forestry assessment tools and their tree inventory to map and quantify the number of ash trees at risk in the city—the first successful use of the technology in a US City environment. Cost-benefit analysis and technology provided the scientific basis for a comprehensive risk-management approach for EAB.

Since 17% of the Milwaukee tree canopy is ash, the impact of the borer was taken very seriously. Staff educated citizens and made direct contact with homeowner with ash trees on private property as early as 2009, three years before the borer was found in Milwaukee in 2012. Treatment of 28,000 ash street trees for EAB began in 2009 along with the more costly approach of

removing dying or physically dangerous infected trees. The city is currently treating 27,000 ash trees in three year cycles. The recognized expertise of City foresters and their EAB treatment approach was recently shared with a team of international scientists visiting from the United Kingdom this June.

The City management approach to prevent future outbreaks of disease and devastating urban forest loss is the implementation of a tree diversity program. By having a variety of tree species, any introduction of a new disease will not wipe out all of the community trees. The goal of creating diversity is to have with time at least four genera of trees per block through tree turnover and the average planting of 4,000 new trees each year. The many varieties of trees will add to the interest of our urban forest and the colors of our seasons.

We can all appreciate the beauty of trees, but the often untold and unseen benefits of trees are their impact on our health, finances and sustainability. According to the I-Tree Ecosystem analysis, the Milwaukee urban forest in 2013 provided $1.8 million in storm water saving annually and removed 569 metric tons of pollution ($18.8 million/year). Some other savings come from storing 14,100 tons/year ($1.1 million) of carbon dioxide by sequestration, and a yearly building energy savings of $1.3 million. The lower noise level, the increase to our property values, the cooling of our streets, the breaking up of urban heat islands and existence of a canopy and habitat for wildlife are but some of the added benefits. The three percent of our City general purpose budget allocated for the City Forestry Section is well spent and provides many returns.

Murray Hill Neighborhood Association thanks the passionate and dedicated Forestry Staff that have added to our quality of life in so many ways in the past, today and in their plans for the future. Keep up the good work!