Early History – Effigy Mound Builder

By Cynthia Sommer

The Native American earthen mounds that still exist in Wisconsin are unique archeological treasures. Conical mounds like the one that still exists in Lake Park are relatively common. Some of the more spectacular mounds are called “effigy mounds” because they take the form of birds, bears, water spirits, panthers, and other forms. Some of the effigy builders made a rare type of earthwork called Intaglios where forms are dug into the earth rather that built above it. There are also a few, rare examples of mounds in Wisconsin that were built in the human form.

Unfortunately, many of the more than 20,000 mounds that once existed in Wisconsin have been destroyed by the growth of cities and the development of farmland. While there are thousands of remaining mounds, these are often under-appreciated or unknown.

Unfortunately, many of the more than 20,000 mounds that once existed in Wisconsin have been destroyed by the growth of cities and the development of farmland. While there are thousands of remaining mounds, these are often under-appreciated or unknown.

The conical mounds in Lake Park may have been built by the Middle Woodland peoples sometime between 500 BC and 400 AD. While earlier societies depended largely on hunting and gathering, by Middle Woodland times horticultural activities provided time for more communal activities beyond the basics of survival. Hunting of deer and elk and the gathering of wild rice was supplemented with squash and corn cultivation. The simple conical mounds are believed to have served a variety of social and ceremonial purposes.

A very rapid change in culture occurred during the time of the Late Woodland Indians around 500 AD as populations increased, technologies evolved, and trade expanded. Within a span of only a couple centuries, a new and distinctive culture that archaeologists call “Effigy Mound Builders” arose in Wisconsin.

After 500 AD the bow and arrow replaced spear and darts as hunting and fighting weapons, better pottery was made and domesticated plants such as squash, corn and, later, beans became prominent in their diet. Wisconsin also had a climate fluctuation around 700 AD that lead to weather that was warmer and wetter in places, conditions ideal for plant growth that increased agricultural yields. A rapid shift to village based living supported the focus on agriculture along with a reorientation of groups or clans to the land and territory. Social relations and ideology changed as new economic and settlement patterns developed.

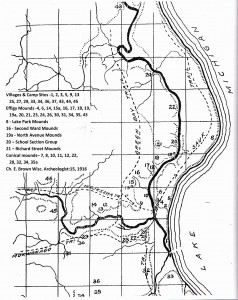

The 1916 map of Milwaukee by the renowned Wisconsin Archeologist Charles E. Brown shows the location of Indian Mounds, village sites and trails at the time of the rapid influx of European settlers in the 1830’s. Increase A. Lapham, a land surveyor and naturalist who arrived in Milwaukee in 1836, is largely responsible for locating most of the mounds in Milwaukee. Lapham was interested in all aspects of natural history and contributed much to our knowledge of Wisconsin’s flora, fauna and geography.

The 1916 map of Milwaukee by the renowned Wisconsin Archeologist Charles E. Brown shows the location of Indian Mounds, village sites and trails at the time of the rapid influx of European settlers in the 1830’s. Increase A. Lapham, a land surveyor and naturalist who arrived in Milwaukee in 1836, is largely responsible for locating most of the mounds in Milwaukee. Lapham was interested in all aspects of natural history and contributed much to our knowledge of Wisconsin’s flora, fauna and geography.

The effigy mounds were usually located along the rivers or lakes; the shapes of the mounds intrigued Lapham and many early settlers. The most common types of effigy mounds depicted birds, bears and the long tailed creatures called panthers, lizards or water creatures. The bird mounds were usually found at a higher elevation of ground than the ground or water animals. These forms of creatures are believed to symbolize animal spirits that fit into the Native American Indian beliefs about a world comprised of Upper (birds) and Lower (water panthers) World beings.

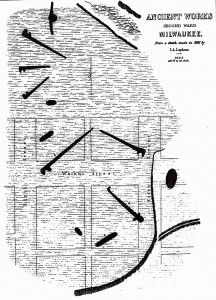

Groups of mounds were located throughout Milwaukee along the rivers with several interesting ones found on the eastside. The impact of the urban growth can be seen in Lapham’s original map of the Second Ward mounds near Walnut and Fifth and Sixth Street that shows twelve mounds including panther, bird and conical shapes. The general location of the Second Ward mounds is #16 on the C. Brown , 1916 map. The nearby North Avenue mounds (#19a; C. Brown, 1916 map) containing a panther and conical form were located near the Milwaukee river south of North Avenue while the seven “School Section” mounds (#20 on 1916 map) were found east of present day Humboldt Avenue, south of Clark Street just north of North Avenue. Lapham, traveling down the Milwaukee river just before North avenue, described “three lizard [panther] mounds [130, 130 and 135 ft. long] and four oblong forms… completely covered with original forest”.

Some of the mounds were used to bury the dead but some did not contain human remains. An artifact, such as a cooking pot or arrow head might be found in the mound but more often no items were included. The shapes of the mounds are believed to represent a specific lineage or clan and not necessarily a person buried within. These people were creating a tangible symbol of their identity. Today’s Native American clans often identify with animal spirits.

Changes came again to Wisconsin’s native peoples around 1000 AD as cultural developments further south spread north. Effigy mounds were replaced by village cemeteries and the cultures that built the mounds evolved. There still remain several fine examples of effigy mounds within an hour’s drive of Milwaukee. Lizard Mound County Park in West Bend has 25 mounds of interesting sizes and shapes; the Sheboygan Indian Mound Park has eighteen effigy mounds and the Indian Mounds and Trail Park in Ft. Atkinson has eleven effigy mounds. Consider taking a day trip to appreciate the efforts of early Native Americans. Imagine the life, culture and beliefs of Wisconsin’s native peoples before Europeans arrived.